UNIVERSIDAD 2024

MULTIVERSE

by Michel J. Meaney, Ph.D. Head of Learning Engineering

Skill-biased Technological Change and the Multiverse Model

The rapid pace of technological change has created a substantial and unmet demand for skilled workers in the digital economy. Traditional education systems struggle to adapt nimbly, leaving businesses with a skills gap that can hinder their growth and innovation. Multiverse is significantly disrupting the education and employment sector by innovating the concept of apprenticeships in order to fill this gap. The company partners with leading businesses to identify their critical skill needs and develop tailored programs that equip apprentices with the knowledge and experience they need to succeed in the digital workplace. Multiverse apprenticeships leverage industry-aligned curriculum, world-class coaches, and advanced digital tools to deliver high quality learning to diverse populations. In doing so, it is striving to build an education model motivated by the belief that the future of work is on-the-job learning.

Context: Skill-biased Technological Change and the Skills Gap

Education – the pursuit of knowledge discovery, preservation, and application – is a central activity of civilization (Menand, 2010). These activities incrementally advance our understanding of phenomena across the breadth of the human experience, from the mysteries of the material world to the factors supporting democracy (White, 2013).

Beneath these ethereal pursuits of education lay more modest and practical aims, nonetheless essential to societal well-being: the development of increasingly advanced modes of economic output and the cultivation of human capital to further economic progress and competitiveness (Carnoy, 2016). In a flourishing society, people from all backgrounds should have the opportunity to gain new knowledge and abilities and to leverage their unique talents and skills to contribute to economic prosperity for themselves, their families, and their communities (Meaney, 2021; Escobari et al., 2019). Providing this opportunity to as many people as possible continues to be a central aspiration for governments and educational systems, a goal they struggle to accomplish equitably and inclusively (for the American perspective, see Carnevale and Strohl 2013; for the global perspective, see Altbach et al. 2009).

Accomplishing this goal amidst accelerating technological change is increasingly difficult. In what has been described as the ‘fourth industrial revolution’ (Schwab, 2017), technological change is changing the nature of the economy, and in doing so, altering the ways in which humans contribute to economic output (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2022; Osbourne and Frey, 2013). As computing costs decline and computational power accelerates, the skills required to succeed in the labour market continue to shift at an ever-increasing pace (Acemoglu and Restrepro, 2020; Meaney and Smith, 2016). In a process termed skill-biased technological change, these labour market shifts cause employers to place increasing premiums for more non-routine skills that are cognitively demanding and require sophisticated interpersonal skills, tasks consider to be higher skill (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2022; Buera, 2022). This has driven wage inequality up dramatically over the past two decades, with historically marginalised groups most negatively impacted (Carnevale et al., 2022). Recent developments in artificial intelligence like ChatGPT and other generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools promise to accelerate this process further and radically disrupt the labour market across a wide range of occupations and industries (Felten, Raj, and Seamans, 2023; Acemoglu et al, 2022). Initial estimates by Goldman Sachs suggest that more than 300 million jobs may be already at risk (Hatzius, 2023).

Businesses are struggling to find the talent they need in this landscape. While historically, there have been reasons to question the nature and causes of the skills gap (Donovan et al., 2022; Modestino et al., 2020), it has been empirically validated that shifts in employment have substituted away from more manual jobs toward more cognitively demanding ones, through both automating lower skill tasks and increasing the productive output of higher skilled ones (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2022; Autor, 2019). As reported by the Financial Times, the UK Chamber of Commerce recently found that while upwards of 65% of firms were hiring, 80% indicated that finding the talent they needed continued to be difficult (Colback, 2023). This is particularly true in IT-related jobs. In another recent survey by Forbes, 93% of British firms reported an IT skills gap, with 42% indicating that this was exacerbated by rapid increase in technology acceleration (Thornhill, 2023). Importantly, these skills gaps do not just imply a shortage of engineers and software developers, but increasingly a wide range of digital experts needed across fields to support digital transformation.

In the US, the skills shortage is similarly acute. According to global research firm Nash Squared, 59% of American technology executives are experiencing a skills shortage (2023). Citing data from the Bureau of Labor and Statistics, the US Chamber of Commerce indicates that there are upwards of 9.5 million job openings in the US, with only 6.5 million unemployed persons (Ferguson, 2023). While this gap is attributable to a variety of factors, one of them is the growing digital skills gap. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and National Skills Coalition, while 92% of jobs in the US require digital skills, 1 ⁄ 3 of the American workforce does not have sufficient digital competency for these roles (Bergson-Shilcock and Taylor, 2023). CompTIA, the technology industry trade group, discovered that pessimism about finding the right talent was one of the top worries of technology executives (2023).

Response of Traditional Higher Education

Globalisation and economic integration are driving more students worldwide to pursue higher education as a path to economic security (Carnoy, 2016; Altbach et al., 2009). Global higher education enrollment has more than doubled since 1992 and is projected to continue surging (World Bank, 2023; Calderon, 2018; Marope et al., 2013). National higher education systems are struggling to keep pace. For instance, India may only be able to accommodate 1/3 of its projected 140 million college-aged students by 2030 (Kim, 2015). The US also faces a potential shortfall of 12 million graduates over the next two decades (Carnevale and Rose, 2015). This imbalance in supply and demand disproportionately affects disadvantaged students who face barriers to access, even as higher education becomes more critical for economic mobility (Carnevale et al., 2022; Reardon, 2018; Reardon, 2011).

The introduction of AGI accelerates these trends further. McKinsey & Company estimates that by 2030, 30% of tasks in US occupations alone may be automated, with some 12 million occupational transitions needed (Ellingrud et al., 2023). A recent survey by Jobs for the Future indicates that more than half of American adults believe AI will impact their jobs and that they need upskilling to navigate these changes; furthermore, 88% doubt their employers will provide the training they need (Jobs for the Future, 2023). According to a recent article in the Harvard Business Review, the half life of a skill is now just five years, and only two-and-a-half years for many technology-intensive roles (Tomayo et al., 2023). Globally, the World Economic Forum (WEF) believes that 44% of jobs will be disrupted by AI in the next five years (2023).

Traditional forms of higher education struggle not only to meet demand gaps in terms of output, but increasingly in terms of the skills and behaviours needed to thrive in the workplace – especially in the areas of professional development goals and social and emotional skills (Goulart et al, 2021). University models of education struggle to adapt in the context of rapid digitization, and the demand for more flexible, shorter, and more industry aligned opportunities continues to grow (O’Donnell, 2023). There is also debate in higher education of whether these adaptations should even be pursued (Davey and Harney, 2023), given the goals of higher education extend beyond mere employability. As AGI begins to make these needs more acute, the traditional higher education system alone will continue to struggle to respond. Given the breadth and pace of disruption facing the labour market, a concerted effort to support workers in retraining and skill matching is needed to facilitate economic opportunities (Ellingrud et al., 2023). Even more concerning is that the jobs most exposed to automation are held by workers that are historically far less likely to pursue education and training opportunities outside of work (Laguna-Muggenburg et al., 2021; Nedelkoska and Quintini, 2018). This will require growth and adaptation among higher education, but it will also require new models that can deliver training in a flexible manner, with speed and scale to meet the demand.

Multiverse

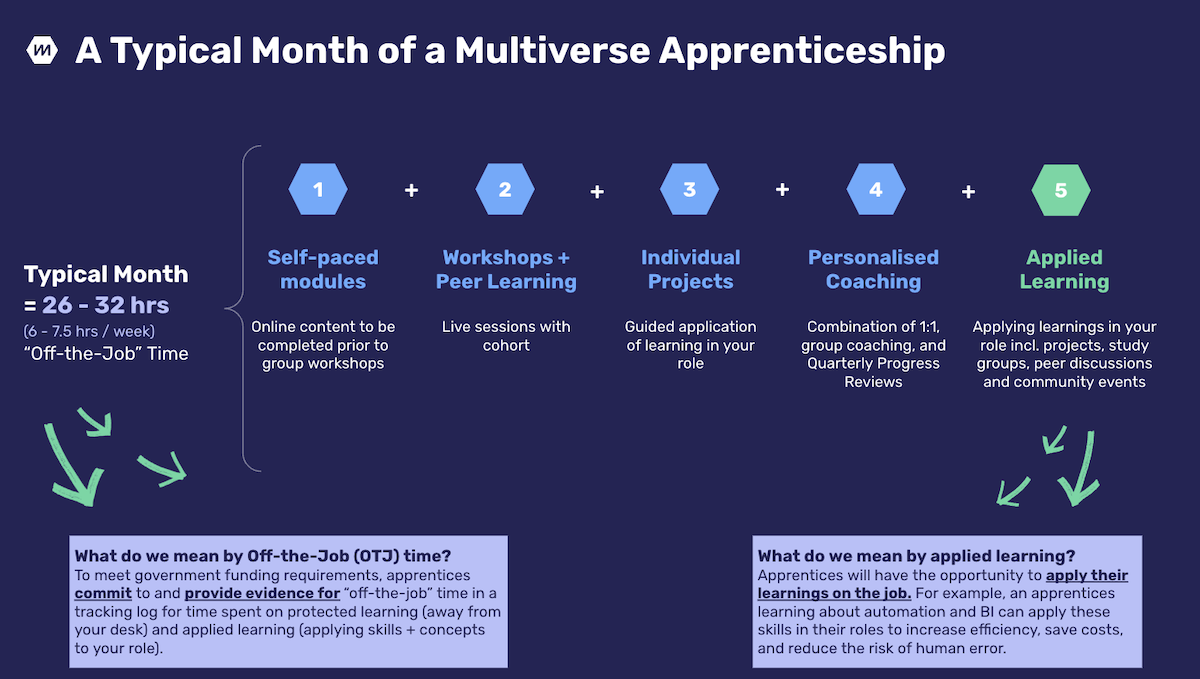

Founded in 2016, Multiverse partners with leading tech firms to identify specific skill needs and co-designs bespoke apprenticeship programs for those firms. This learn-by-doing model aims to equip apprentices with immediately relevant skills for in-demand roles. Multiverse’s core offering is a tech apprenticeship program spanning 1-2 years, tailored to employer partners’ needs. Apprentices spend 80% of their time working on the job and 20% in supplemental training. To bridge the gap between coursework and work-based learning, apprentices log work time that applies concepts from their coursework, deepening their skills by directly applying relevant learning. Coursework combines technical skills like software engineering and data science with soft skills like communication and critical thinking.

This learn-by-doing approach contrasts traditional classroom-based technology education. Rather than pursuing broad computer science degrees, Multiverse apprentices gain targeted skills for employer needs. This demand-driven model maximises apprentices’ job-readiness upon completion.

Multiverse’s team of industrial organisational psychologists develop proprietary tests for identifying and validating skills gaps, assessing candidate role fit, and ultimately that guide the admissions process. These experts also develop formative and summative assessments to provide apprentices feedback and measure mastery of learning outcomes.

These assessments are paired with an internal content and curriculum development team. Composed of former educators, learning scientists, designers, and engineers, the Multiverse curriculum is built to support applied learning and delivered through a world class learning management system (LMS) and instructor-led workshops. Learning is always related to on-the-job tasks, so that apprentices are receiving rigorous development directly aligned to their employer’s needs.

The applied learning focus of the Multiverse programs is one of the reasons their apprentices drive value in just a 13 month program, all while an apprentice is earning a salary and accumulating zero debt, as the cost is covered by the employer. The value proposition is clear compared to 3-4 year university programs, which can require tens of thousands of dollars in debt, and do not come with a direct link to employment during and after graduation.

Upon completion of the program, apprentices are awarded a Multiverse certification which verifies competence across the skills delineated in the program of enrollment. In the UK apprentices complete an End Point Assessment, an assessment by an impartial, third party assessor that verifies the correct skills, knowledge, and behaviours have been developed in accordance with the apprenticeship standard.

Employer partnerships

A core pillar of Multiverse’s model is its extensive partnerships with leading technology firms and other organisations. Partners co-design the curriculum and host apprentices on site, offering perspectives on skills needed for specific roles. Major partners include Facebook, Morgan Stanley, Accenture, CapGemini, and BT Group. Through these relationships, Multiverse gained early traction, facilitated by the UK’s robust apprenticeship system.

Employers work with Multiverse to develop customised workforce readiness plans and curriculums that directly fill their skills gaps. Multiverse has an in-house workforce consultancy team that conducts extensive stakeholder interviews, executive workshops, and skills assessments. These foundational insights are then used to build a set of recommendations and roadmap for clients to pursue, tied to business outcomes and impact to the bottom line.

Apprentices experience a decrease in idle time on the job by 50%, saving more than six working weeks per year for employers. Some 69% of apprentices report gaining new job responsibilities after completion of their apprenticeship. And 93% remain at their company post apprenticeship (Multiverse, 2023).

Coaching and Community

Another differentiating element of the Multiverse offering is the coaching model. The Multiverse coaching model revolves around providing comprehensive and continuous professional development for their apprentices. This is achieved through a combination of 1:1 coaching, interactive group sessions, regular development workshops, and a curriculum that aligns with the requirements of modern businesses across various sectors. These sessions vary from 30 minutes to two hours,

Additionally, each apprentice assigned to a partner company is also assigned a personal coach, who guides them through their professional journey. These coaches are responsible for providing ongoing professional and personal support, helping the apprentice to navigate their new job, develop key skills and grow within their role. By focusing on regular, direct interaction with their apprentices, Multiverse is able to provide tailored advice and guidance, ensuring that each apprentice feels supported and engaged throughout their apprenticeship.

To scale the coaching model even further, Multiverse is in the process of building advanced technical products and AI solutions designed to assist coaches with tasks like creating and evaluating assignments, and formulating personalised study plans for apprentices. The product team at Multiverse builds these tools to help maximise the impact of coaching while ensuring that every apprentice gets differentiated support. Real-time data and insights about apprentice progression enables timely, targeted interventions to be deployed at scale when apprentices need them. One-size-fits-all models neglect the unique needs of each student. Rich data profiles paired with access to asynchronous resources and coaching support as needed helps ensure each apprentice receives the support they need. These tools will help further unlock coaches time for apprentice support.

The company also places a strong emphasis on community-building. Through networking events and socials, the apprentices are given opportunities to build professional relationships that can bolster their career progression. This holistic, supportive coaching model is designed to empower apprentices, equipping them with the knowledge, skills, and confidence to succeed in their chosen career path.

For adult learners, coaching and community are pivotal for ensuring that apprentices are adequately supported, and these structures also promote persistence, completion, and on-the-job skill application. Research indicates that adult learners in particular are motivated by learning skills that directly apply to advancement in the workplace (Knowles, 2013). They thrive in group learning environments where they can learn from other professionals (Escobari et al., 2019). And they sometimes require additional support for how to navigate barriers to completion from juggling work with other life responsibilities (Wildavsky, 2021). The Multiverse model is attentive to these realities in ways that traditional adult learning programs might neglect.

Results

Multiverse’s rapid growth signals its potential to reshape technology talent development and hiring. Its employer-driven model represents a paradigm shift from traditional education pathways focused on broad theoretical learning. Work-integrated learning helps address the skills gap by imparting immediately relevant, job-tailored skills.

Multiverse counts more than 15,000 apprentices worldwide as alumni or on-program learners, and has partnered with over 1000 businesses to fill their talent gaps. This translates to over $660 million in cost-saving or revenue generating activities. Furthermore, Multiverse reports an 85% program completion rate and a 93% job placement rate for graduates (Multiverse, 2023).

If scaled significantly, Multiverse could help diversify tech and expand career opportunities for non-college graduates. Current university computer science programs graduate fewer than 65,000 students per year in the US and UK combined (Kemp 2022, HESA 2022). Multiverse aims to enable 1 million apprentices by 2030, which could greatly increase qualified labour supply.

Author: Michel J. Meaney, Ph.D.

Head of Learning Engineering at Multiverse

Universidad 2024 was created in collaboration with:

The Proeduca Group

PROEDUCA’s objective is to provide the best online higher education to its students and it achieves this through educational commitments at three universities: The International University of La Rioja, the Online University of Mexico (UNIR Mexico), and CUNIMAD. It also offers studies located in Peru, at the Newman Postgraduate School, and in the United States, where it has a presence through MIU City University Miami.

Works Cited

Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2022). Tasks, automation, and the rise in us wage inequality. Econometrica, 90(5), 1973-2016. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA19815

Acemoglu, D., Autor, D., Hazell, J., & Restrepo, P. (2022). Artificial intelligence and jobs: evidence from online vacancies. Journal of Labor Economics, 40(S1), S293-S340. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/718327

Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2020, May). Unpacking skill bias: Automation and new tasks. In AEA Papers and Proceedings (Vol. 110, pp. 356-361). 2014 Broadway, Suite 305, Nashville, TN 37203: American Economic Association. DOI: 10.1257/pandp.20201063

Altbach, P. G., Reisberg, L., & Rumbley, L. E. (2019). Trends in global higher education: Tracking an academic revolution (Vol. 22). Brill.

Autor, David H. 2019. “Work of the Past, Work of the Future.” AEA Papers and Proceedings, 109: 1-32. DOI: 10.1257/pandp.20191110

Bergson-Shilcock, A., & Taylor, R. (2023). Closing the Digital” Skill” Divide: The Payoff for Workers, Business, and the Economy. National Skills Coalition. https://nationalskillscoalition.org/resource/publications/closing-the-digital-skill-divide/

Buera, F. J., Kaboski, J. P., Rogerson, R., & Vizcaino, J. I. (2022). Skill-biased structural change. The Review of Economic Studies, 89(2), 592-625. https://academic.oup.com/restud/article-abstract/89/2/592/6332019

Calderon, A. (2018). Massification of Higher Education Revisited. Melbourne: RMIT University.

Carnoy, M. (2016). Educational Policies in the Face of Globalization: Whither the Nation State?. Handbook of Global Education Policy, 27. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118468005.ch1

Carnevale, A. P., Campbell, K. P., Cheah, B., Gulish, A., Quinn, M. C., & Strohl, J. (2022). The Uncertain Pathway from Youth to a Good Job: How Limits to Educational Affordability, Work-Based Learning, and Career Counseling Impede Progress toward Good Jobs. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED624515

Carnevale, A. P., & Strohl, J. (2013). Separate & unequal: How higher education reinforces the intergenerational reproduction of white racial privilege. https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/1050297

Carnevale, A. P., & Rose, S. J. (2015). The Economy Goes to College: The Hidden Promise of Higher Education in the Post-Industrial Service Economy. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/the-economy-goes-to-college/

Colback, L. (2023). Technology and the Skills Shortage. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/b1b710a1-6d12-43e5-8508-ae4584a7289a

CompTIA. (2023). CompTIA IT Industry Outlook 2023. https://www.comptia.org/content/research/it-industry-trends-analysis

Davey, S., & Harney, B. (2023). Higher Education and Skills for the Future (s) of Work. In The Future of Work: Challenges and Prospects for Organisations, Jobs and Workers (pp. 111-125). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31494-0_8

Donovan, S. A., Stoll, A., Bradley, D. H., & Collins, B. (2022). Skills Gaps: A Review of Underlying Concepts and Evidence. CRS Report R47059, Version 3. Congressional Research Service.

Ellingrud, K., Sanghvi, S., Madgavkar, A., Dandona, G. S., Chui, M., White, O., & Hasebe, P. (2023). Generative AI and the future of work in America. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/generative-ai-and-the-future-of-work-in-america

Escobari, M., Seyal, I., & Meaney, M. (2019). Realism about Reskilling: Upgrading the Career Prospects of America’s Low-Wage Workers. Workforce of the Future Initiative. Center for Universal Education at The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/realism-about-reskilling/

Felten, E., Raj, M., & Seamans, R. (2023). How will Language Modelers like ChatGPT Affect Occupations and Industries?. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.01157.

Ferguson, S. (2023). Understanding America’s Labour Shortage. The US Chamber of Commerce. https://www.uschamber.com/workforce/understanding-americas-labor-shortage

Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. (2013). The Future of Employment.

Goulart, V. G., Liboni, L. B., & Cezarino, L. O. (2022). Balancing skills in the digital transformation era: The future of jobs and the role of higher education. Industry and Higher Education, 36(2), 118-127. https://doi.org/10.1177/09504222211029796

Jobs for the Future. (2023). Majority of Workers Report They Need New Skills to Prepare for AI’s Future Impact. https://www.jff.org/majority-workers-report-they-need-new-skills-prepare-ai-future-impact/

Kim, J. (2015). Coursera, Apple, and the Future of Global Higher Education. Inside Higher Education. https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/technology-andlearning/courseraapple-and-future-global-higher-education

Knowles, M. (2013). Andragogy: An emerging technology for adult learning. In Boundaries of adult learning (pp. 82-98). Routledge.

Hatzius, J. (2023). The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth (Briggs/Kodnani). Goldman Sachs. https://www.gspublishing.com/content/research/en/reports/2023/03/27/d64e052b-0f6e-45d7-967b-d7be35fabd16.html

HESA (Higher Education Statistics Agency). (2022). Higher Education Student Statistics: UK, 2020/21. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/17-01-2022/sb258-higher-education-student-statistics

Laguna-Muggenburg, E., Bhole, M., & Meaney, M. (2021). Understanding Factors that Influence Upskilling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.12193.

Marope, P. T. M., Wells, P. J., & Hazelkorn, E. (Eds.). (2013). Rankings and accountability in higher education: Uses and misuses. Unesco. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000220789

Meaney, M. (2021). Essays on the design of inclusive learning in Massive Open Online Courses, and implications for educational futures (Doctoral dissertation, University of Cambridge). https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.76128

Menand, L. (2010). The marketplace of ideas: Reform and resistance in the American university. WW Norton & Company.

Modestino, A. S., Shoag, D., & Ballance, J. (2020). Upskilling: Do employers demand greater skill when workers are plentiful?. Review of Economics and Statistics, 102(4), 793-805. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00835

Multiverse. (2023). Impact Report. https://www.multiverse.io/en-US/impact-report-2023

Nash Squared. (2023). The Digital Leadership Report 2023. https://www.nashsquared.com/dlr-2023/dlr-2023

Nedelkoska, L. and G. Quintini (2018), “Automation, skills use and training”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 202, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/2e2f4eea-en

O’Donnell, P. (2023). Apprenticeships on the Rise. Education Next, Vol. 23, No. 3. https://www.educationnext.org/apprenticeships-on-the-rise-burgeoning-alternative-challenges-college-for-all-mentality/

Reardon, S. F. (2018). The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor. In Inequality in the 21st Century (pp. 177-189). Routledge.

Reardon, S. F. (2011). The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor: New evidence and possible explanations. Whither opportunity, 1(1), 91-116. https://cepa.stanford.edu/content/widening-academic-achievement-gap-between-rich-and-poor-new-evidence-and-possible-explanations

Roser, M., & Ortiz-Ospina, E. (2013). Tertiary education. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/tertiary-education

Schwab, K. (2017). The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Crown Publishing Group, USA.

Smith, J., & Meaney, M. (2016). Lifelong learning in 2040. The Roosevelt Institute, The Next American Economy Learning Series, 1-8. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/lifelong-learning-in-2040/

Thornhill, J. (2023). IT Skills Gap Report 2023. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/uk/advisor/business/software/digital-skills-gap/

Tamayo, J., Doumi, L., Goel, S., Kovács-Ondrejkovic, O., and Sadun, R. (2023). Reskilling in the Age of AI. Harvard Business Review 101, no. 5: 56–65. https://hbr.org/2023/09/reskilling-in-the-age-of-ai

White, J. (2013). Philosophy, philosophy of education, and economic realities. Theory and Research in Education, 11(3), 294-303. https://doi.org/10.1177/14778785134981

Wildavsky, B. (2021). Meeting the Needs of Working Adult Learners. The Chronicle of Higher Education Inc and Guild Education. https://connect.chronicle.com/rs/931-EKA-218/images/ServingPostTraditionalStudents_GuildEducation.pdf

World Bank (2023) – processed by Our World in Data. Gross enrolment ratio in tertiary education [dataset]. World Bank, World Bank Education Statistics (EdStats) 2023 [original data]. Retrieved December 4, 2023 from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/gross-enrollment-ratio-in-tertiary-education

World Economic Forum. (2023). Future of Jobs Report. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-jobs-report-2023/